Putting a value on financial advice

I am mostly a passive investor in index funds and ETFs, and I self-manage all of my investment accounts, including my brokerage accounts and retirement accounts. Much of this blog is devoted to documenting that process and things that I’ve learned along the way.

I previously wrote an article on whether you need a financial advisor or not. It’s fun to read my older articles, not only to see if my writing has improved over time (I’d like to think so, but I’m not sure), but also to see if my opinions have evolved as well. Anyway, to summarize, in that article my general attitude towards financial advisors is that they’re unnecessary and just siphon off your returns. Nonetheless, if you want a financial advisor, make sure they have the right credentials, have fiduciary duty, and that their fees are upfront and transparent.

My framework when writing that article was that financial advisors will cost you money, but some people are happy to pay that cost to outsource a service. During the current bear market and inflationary environment, many people have been asking me various financial questions. Clearly, people want financial advice, even if they don’t necessarily want a financial advisor. The need for financial advising won’t be going away anytime soon.

Can advisors add value?

Another aspect I did not seriously consider is that financial advisors might add value. DIY index investors are usually pretty convinced that their method is superior. But recently, I stumbled across an article from Vanguard titled Putting a value on your value: Quantifying Advisor’s Alpha. The paper attempts to quantify the value added by a financial advisor. To my surprise, Vanguard reports that they believe financial advisors can add up to 3% in net returns. Other companies have published similar studies, but Vanguard’s was the most notable to me because, well, it comes from Vanguard.

When it comes to investing, 3%, or 300 basis points, is a staggering amount. For example, the difference between 7% and 10% returns over time defies belief. An investment that compounds for 35 years at 10% will have approximately triple the value of one that compounds at 7%. This discrepancy only grows even larger over time. It’s hard for us to imagine because we’re so used to thinking linearly and not exponentially in our daily lives.

Compounding magnifies small differences in returns over long time horizons. In this example, after 35 years, a 3% difference in returns becomes a three-fold difference in portfolio value.

In fact, beating the market consistently is so incredibly difficult that even a small alpha, such as 1%, is a remarkable achievement in the long term. Fund managers who can achieve persistent alpha for years become Wall Street legends and run funds with billions of dollars under management. By the way, this is the same argument for why investing fees are so insidious. A mutual fund with 1% expense ratio will almost certainly underperform a low-cost index fund in the long run as that 1% eats away at your compounding returns.

How do advisors add value?

So how can a financial advisor add 3% in net returns? My interest piqued, I took a closer look at Vanguard’s paper to see if we’re all missing out for not having a Vanguard financial advisor.

First, I should point out that the paper is authored by 5 financial advisors. Obviously, they’re going to argue in favor of financial advising. I don’t expect anyone to trash their own profession or advocate for their own uselessness. For example, there exists an movement known as anti-psychiatry which argues that psychiatric diagnoses are not valid and psychiatric treatment does more harm than good. Even if, on some objective grounds, those arguments had merit, you wouldn’t find me espousing them as a psychiatrist.

In that context, I would say the authors put forth a valiant argument. From the outset, they acknowledge that quantifying the value added by a financial advisor is very difficult. The paper directly states that advisors are not likely to provide better returns than the market itself, due to long-standing research that shows actively managed investments do not beat the index over time.

Therefore, advisors do not have secret investments with 3% better returns than the market, period. Instead, that 3% has to come from elsewhere. The paper suggests seven categories where a financial advisor can add value, and the approximate “value added" in each category:

Source: Vanguard

I’ll only cover each category briefly, as interested readers should just read the arguments in the paper itself. Their overall premise is reasonable, although it requires a lot of heavy hand-waving to get to 3%. I should also note that at several points in the paper, the authors do acknowledge that the 3% value add is not likely to be realized annually, but will likely be sporadic. At other places, however, they label various estimates for value add as annual or annually.

Asset allocation. This describes the percentages of a portfolio allocated to various assets, such as stocks, bonds, cash, and alternative investments. Asset allocation is extremely important for every investor, although there is no single correct allocation for everyone. The paper correctly argues that proper asset allocation adds value, although the amount of value added is impossible to quantify.

Cost-effective implementation. Vanguard estimates that this adds 34 basis points (0.34%). The idea here is that financial advisors can help identify lower-cost investments and help reduce the overall cost of a portfolio, thereby boosting returns. In theory, this is correct: investing research has shown, time and time again, that the less you pay, the more you keep. In fact, Vanguard pioneered the low-cost index funds which millions of people use today to invest and build wealth. The irony here is that many financial advisors derive their commissions from pushing high-cost, front-loaded mutual funds onto their clients. If you’re already invested in low-cost Vanguard index funds, there is simply no room to cut costs further.

Rebalancing. Vanguard estimates that this adds 26 basis points (0.26%). Asset allocation drifts over time as asset classes perform differently, so investors must actively rebalance their portfolio to maintain their allocation. This is something that many passive investors (myself included) are remiss in doing. If appropriate asset allocation is important, it follows that maintaining that allocation over time must be equally important.

Behavioral coaching. Vanguard estimates this adds 150 basis points (1.5%), which is by far the largest portion of an advisor’s value add. They’re not wrong: especially in turbulent times, such as the current market, behavioral coaching can add tremendous value. Investors stand to lose far more by making rash or impulsive decisions than from market volatility itself. More likely than not, financial advisors will tell clients with long time horizons to stay the course. More on this later.

Asset location (not to be confused with asset allocation). Vanguard estimates this adds up to 75 basis points (0.75%). The premise here is that there are ways to maximize tax-efficient investing. For example, because capital gains are not taxed until they are realized, but dividends are always realized and taxed in the year they are received, it is better to put income-producing assets into tax-advantaged accounts and growth assets into taxable accounts, while still maintaining your desired overall portfolio asset allocation. The main caveat to this is that tax-advantaged accounts are constrained in size and contribution limits compared to taxable accounts, and, depending on your employer, the investment choices in your tax-advantaged accounts may be limited as well.

Withdrawal order. Vanguard estimates that this adds up to 110 basis points (1.1%). Here, Vanguard is referring to the optimal way to spend down a portfolio in retirement to maximize tax efficiency for those withdrawals. Obviously, this does not apply to any investor in the accumulation phase, which is pretty much everyone who isn’t retired. Even if the correct withdrawal order can add a full 110 basis points, the value added here has much less time to compound and make a difference. The true annualized value of withdrawal order optimization over the lifetime of an investor (for example, 35 years of accumulation then 20 years of withdrawals) will be much less than Vanguard’s estimate.

How much value do I think advisors add?

Given Vanguard’s framework, I can see the arguments for each value add category. However, I think the overall conclusion that advisors add 3% net returns in value is rather optimistic. The 1.1% value add for withdrawal order is irrelevant to most investors, who are accumulating. The 0.34% value add for cost-effective implementation seems ironic. While I can envision a scenario where a clueless investor will save on fees after their portfolio is scrutinized by an advisor, this simply does not apply for savvy index fund investors because there is simply no further cost-savings to be had.

The asset location and rebalancing arguments do hold significant merit. Much as been written about tax-efficient investing, which is beyond the scope here. I can see where a financial advisor can add value in these areas, if an investor was unwilling or unable to do it themselves.

But by far the largest portion of the value add, as admitted in the paper, is from behavioral coaching. This deserves some further discussion, as we all know behavior can greatly influence finances on both a macro level (markets) and on a personal level. In fact, behavior probably accounts for more of an investor’s returns during a lifetime than just about any other factor, including economic and market conditions. This is especially true during turbulent conditions, such as the current market.

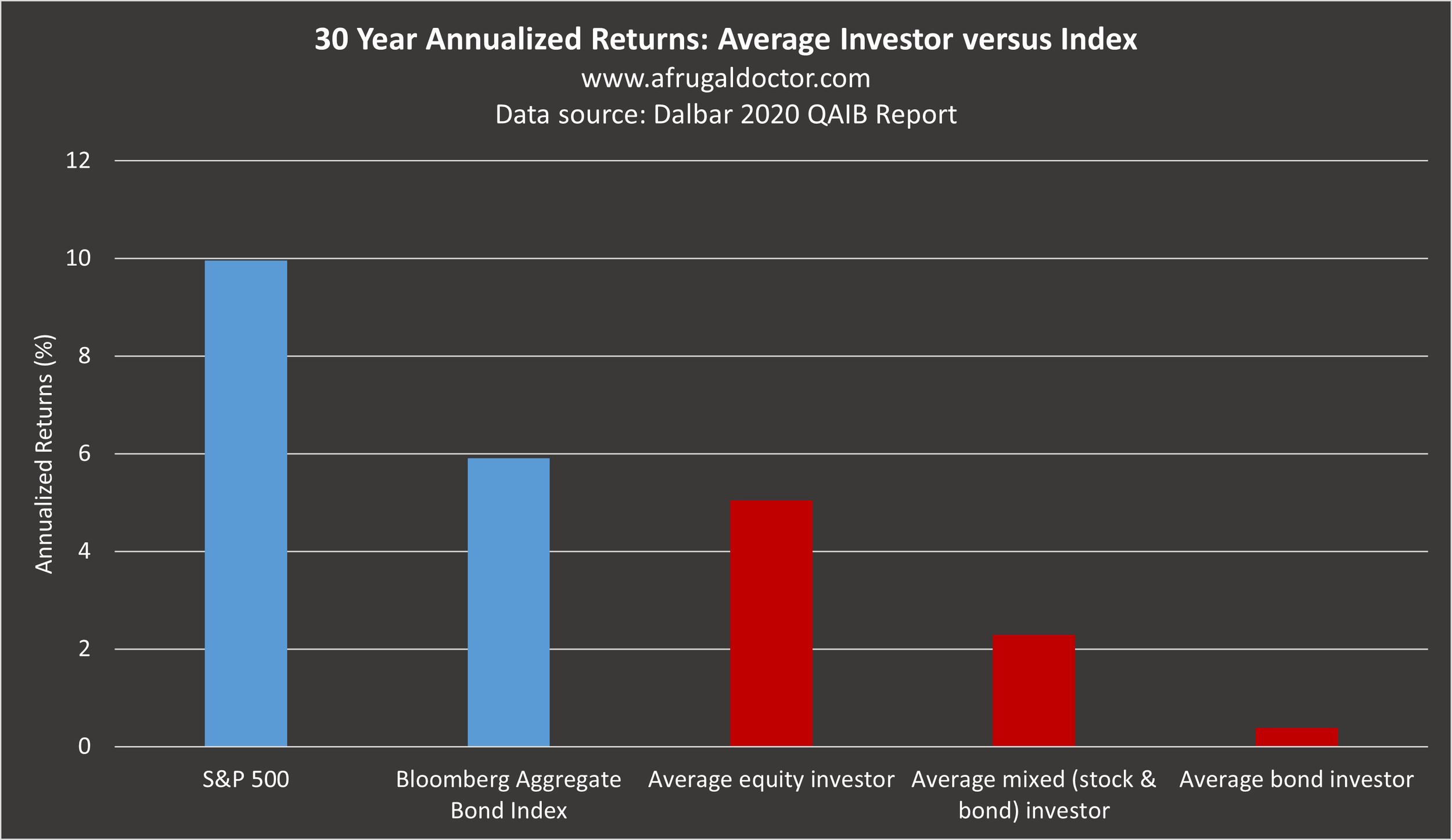

Plenty of data supports this assertion. The Dalbar Quantitative Analysis of Investor Behavior (QAIB) report, published since 1984, has consistently found that the average investor far underperforms the market index.

The average investor far underperforms the market index. Data from “Quantitative Analysis of Investor Behavior, 2020,” DALBAR, Inc. www.dalbar.com.

These results are pretty shocking. In the 2020 QAIB report, the S&P 500 had 30-year annualized returns of about 10%, whereas the average stock investor managed only half of that at about 5%. If you consider the fact that any investor can match the S&P 500 returns by investing in an S&P 500 index fund, you really have to wonder what the heck the average investor is doing. Much of this has to do with investor behavior.

According to the report:

“One major reason that investor returns are considerably lower than index returns has been the fact that many investors withdraw their investments during periods of market crises. Since 1984, approximately 70% of this underperformance occurred during only ten key periods. All of these massive withdrawals took place after a severe market decline.”

So I am more than convinced that behavioral coaching is worth 1.5% returns. For some people, it’s probably worth far more than that. But at the same time, it’s hard for me to justify paying 1.5% of assets in fees for behavioral coaching. It just seems so… simple.

Here, I am reminded of the late comedian Bob Newhart’s classic psychotherapy skit, where he plays a therapist who repeatedly yells at a client to simply “stop it!” as the solution to all her anxieties.

I do not own this youtube account or video.

Of course, the catch is that psychology and psychotherapy are not that simple, but “pop psychology” sometimes tends to mislead the public into thinking that it is.

At the risk of sounding ignorant, however, I believe that “pop finance” is indeed very simple. The investor equivalent of “Stop it!” is probably something like “Stay the course!”. Even when we expand that a bit, it always boils down to the same few points:

Live within your means.

If in debt, pay it off. If not in debt, do not take on debt.

Invest a portion of every paycheck automatically.

Invest in low-cost index funds. Diversify. Do not pick stocks.

Do not time the market.

Stick to your plan for 30 years regardless of what happens.

Authors far more eloquent than me have endorsed variations of these points, buttressed with amusing or astonishing anecdotes to drive the message home. I don’t have any of those today. Sure, there are some nuances here and there, but for most people, I believe that this is about as good any “behavioral coaching” you’ll get from a financial advisor.

Conclusion

Most investors are their own worst enemy. As it turns out, Vanguard believes the majority of the added value of a financial advisor comes not from some deep technical expertise of financial markets or access to any specific tools. Rather, it comes from behavioral coaching. You’re actually hiring a therapist of sorts to yell some variation of “stay the course!” or “stick to your plans!” at you. For a long-term, buy-and-hold investor who is already investing in index funds and intends to keep investing for decades, I still feel that financial advisors add very little value, and that value likely is negative once advisory fees are taken into account. However, the further you stray from this paradigm as an investor, the more value that advisory services will potentially add. How rattled were you by the global financial crisis? The COVID-19 recession? The current bear market? How strongly do you believe in your ability to stomach a downturn? Has your risk tolerance ever been seriously tested? The current bear market is the perfect time for every investor to do some real introspection and decide if a financial advisor is right for you.

Happy investing!

Another year in the books