Japan’s Lost Decades: 30 years of negative returns from the Nikkei 225

Many investors assume that stocks will keep going up in the long run.

The U.S. stock market, as measured by the S&P 500, or a total stock market index, has never failed to recover from any downturn. In any given year, the market can be down 10%, 20%, or even 30% or more. But it’s pretty rare for the market to remain down after 5 years or longer. As it turns out, over long enough time periods, the investor has always made money. The main question is whether you’re patient enough to wait out a market crash.

How long is long enough? Here’s a nice visualization, originally posted by The Measure of a Plan:

Image from The Measure of a Plan.

As you can see, the U.S. stock market has negative returns in approximately one out of four years. But as your time horizon lengthens, the likelihood of negative returns over that time decreases. There has never been a 20-year period of negative real returns in the history of the U.S. stock market. This means that even if you were exceptionally unlucky in timing your entry into the market, you still made money after 20 years. In fact, the U.S. stock market averages about 9 - 10% nominal annualized returns (before inflation) and 6 - 7% real annualized returns (adjusted for inflation), depending on when you start calculations. The following table shows S&P 500 returns over the last 90 years:

| Decade | Nominal annualized returns (CAGR) with dividend reinvestment |

Real annualized returns (CAGR) adjusted for inflation |

| 1930s | -0.05% | 2.10% |

| 1940s | 9.17% | 3.45% |

| 1950s | 19.35% | 16.94% |

| 1960s | 7.81% | 5.37% |

| 1970s | 5.86% | -1.12% |

| 1980s | 17.55% | 11.42% |

| 1990s | 18.21% | 14.77% |

| 2000s | -0.95% | -3.42% |

| 2010s | 13.56% | 11.58% |

| Total (1930 - 2019) | 9.82% | 6.57% |

Therefore, there’s a widespread belief that although short-term stock market returns can be quite volatile, long-term annualized returns are consistent. Many people just assume that the U.S. market will you 10% per year in your lifetime (I am also guilty of this). Also, as I’ve outlined in a previous post, there is no reasonable scenario where the U.S. stock market ever goes to zero.

This is why the typical advice given to most young investors is something along these lines:

“Invest as much as you can into low-cost, diversified index funds over the course of 20, 30, or even 40 years. Let compound returns do the rest.”

But is there any basis to the belief that the market will always go up over time? Is the U.S. market somehow exceptional or immune to stagnation? The truth is that attempts to predict, forecast, or model market returns have confounded academics and mathematicians for decades, since market returns do not neatly fit any simple models or common probability distributions. Some have even described market returns as essentially random.

Nonetheless, U.S. stocks have gone on an almost uninterrupted bull run since 2009, and with the market reaching new all time highs seemingly every week, speculation that the market is in a bubble never ceases. Can a bubble become so big that when it bursts, the recovery takes so long that an investor will not recover in their lifetime? And what if that were to happen to us, in our own lifetime?

One of my colleagues at work basically asked me this: "Investing in S&P 500 index funds is great and all, but what if the U.S. stock market does what Japan’s stock market did?”

Nikkei 225

She is, of course, referring to the Nikkei 225, which is a price-weighted stock index comprising of 225 publicly traded Japanese companies on the Tokyo Stock Exchange. In many ways, the Nikkei 225 is like the Japanese Dow Jones. It is not entirely comparable to the S&P 500, because the S&P 500 is a cap-weighted index rather than a price-weighted index. Nonetheless, in 1990, the Nikkei 225 crashed in one of the most spectacular stock market collapses in history: the Japanese asset price bubble.

Nikkei 225 index. The “resolution” of data is monthly. Data from Nikkei.

This chart is quite sobering. After a decade-long bull run throughout the 1980’s, the Nikkei 225 index reached an all-time high of 38,915 on December 29, 1989, the last trading day of the year. Probably few could have imagined, on New Year’s Eve of 1989, that the index would be lower 32 years later. As the New Year arrived, the bubble burst. In 1990, the index closed at 23,848 after losing over 38% of its value. This was followed by a minor loss in 1991, but in 1992, the index closed at 16,924 after losing another 26%. But the losses never stopped coming. In fact, in February 2009, almost 20 years(!!) after its all-time high, the index closed at just 7568. And two years after that, in 2011, the index closed for the year at 8,455, which represented its lowest year-end closing value since 1982.

The Nikkei finally began a sustained recovery sometime around 2012. At the end of 2019, the index closed at 23,656, which is still 40% lower than its all-time high from 30 years ago! As of December 2021, the Nikkei sits at 28,792. Some 32 years later, the Nikkei is still 26% lower than its 1989 peak.

The Japanese asset bubble was not limited to Japanese stocks. All Japanese assets, including real estate, were affected, and the entire Japanese economy went into a prolonged decline. This collapse was so devastating that the entire post-1990 period in Japan is now known as the lost decades. In fact, in 1989, 13 of the 20 largest companies in the world by market capitalization were Japanese. Thirty years later, 0 Japanese companies are in the global top 20. You can find a table with more details in my Investing 101 article on why stock picking is hard.

The reasons behind Japan’s incredibly inflated asset prices, subsequent collapse, and decades of economic stagnation are beyond my understanding, so I won’t try to explain them here. Instead, I am here to answer my colleague’s original question, which is now on our collective minds: "Investing in S&P 500 index funds is great and all, but what if the U.S. stock market does what Japan’s stock market did?”

How likely is it to happen in the US?

I have no idea, but my uneducated opinion is that Japan’s situation was unique in many ways, and it is unlikely for the U.S. stock market to undergo a similar experience. While current U.S. stock prices are inflated according to many metrics compared to historical norms, the situation is not comparable to the Nikkei 225 in 1989. At the peak of the Nikkei 225, its price-to-earnings ratio (P/E) was about 60x of trailing twelve-month (TTM) earnings, while the global average trailing P/E for equities was about 15x to 16x. This means that compared to other stocks from around the world, the Nikkei 225 was overpriced by around 4x in 1989, at least when looking at this particular metric.

As of December 2021, the S&P 500 has a TTM P/E ratio of about 27x, which is also higher than historical norms. However, as of December 2021, the global equity TTM P/E ratio is about 20x. For various reasons, all equities have become more expensive compared to their earnings across the board. The S&P 500, while possibly overvalued, isn’t much of an outlier compared to the rest of the world, unlike the Nikkei in 1989. Maybe this is the new normal for equity valuations, or maybe the entire world is a bubble, slowly getting bigger.

Regardless, let’s pretend that over the next 30 years, the S&P 500 follows the same trajectory as the Nikkei 225 did starting at its peak on December 29, 1989. What will that mean for us?

Nikkei total returns

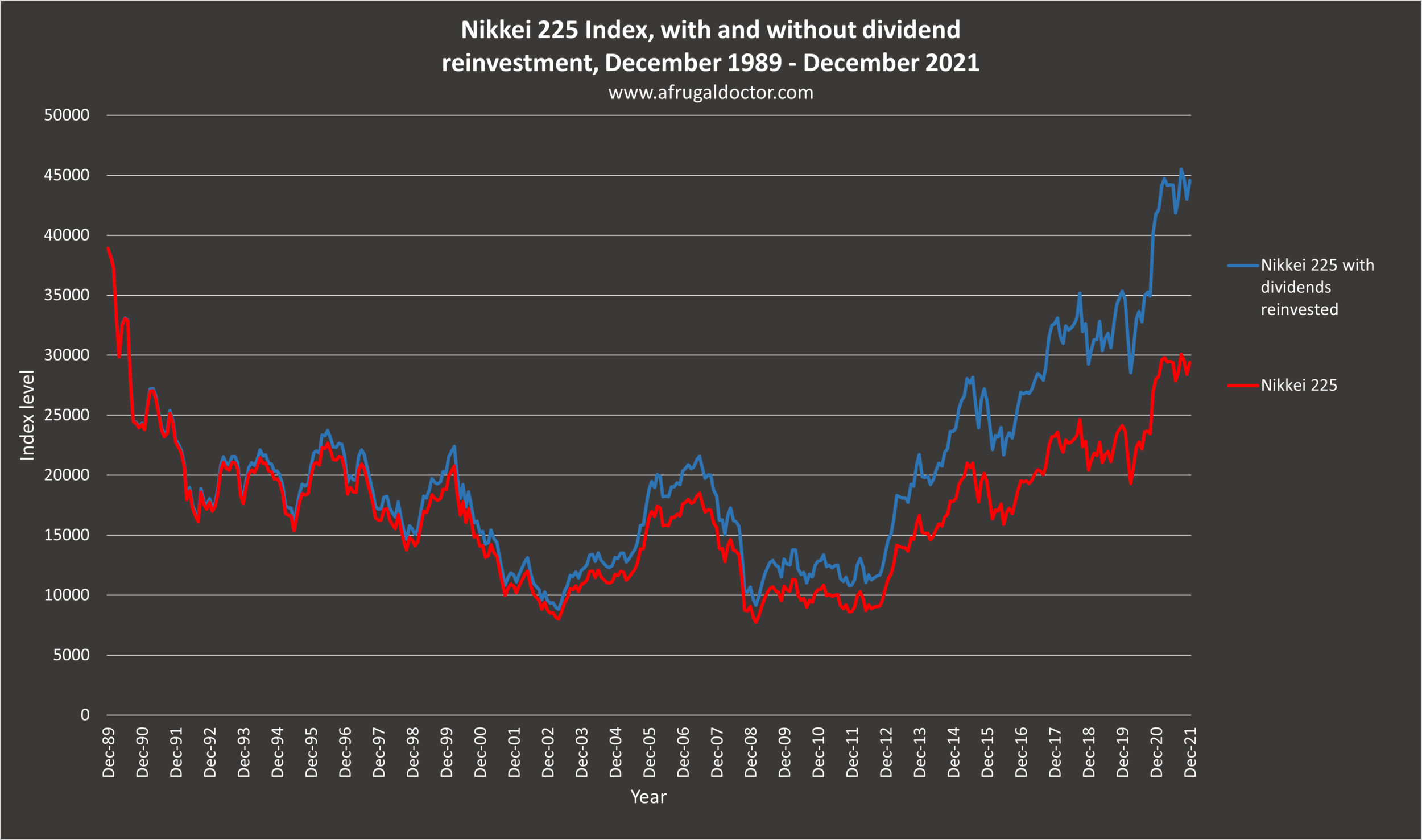

First, it’s important to recognize that the price of the Nikkei index itself does not represent total investment returns! Over long time periods, dividends and dividend reinvestment make up a large component of overall returns. We must look at Nikkei 225 total returns over this time period, rather than just the Nikkei 225 price index itself.

Nikkei 225 with and without dividend reinvestment. Data on Nikkei 225 total returns are from https://indexes.nikkei.co.jp/en/nkave/index/profile?idx=nk225tr (post-2011) and https://dqydj.com/nikkei-return-calculator/ (pre-2011). The “resolution” of data used is monthly.

Of course, even with dividend reinvestment, this was an unquestionably a terrible period for Japanese investors. But it is slightly less bleak than looking at the price index itself. If we started at the peak of the Nikkei 225 in December 1989, the total return as of December 2019 (30 years later) is -9.07%, which comes out to annualized returns of -0.32%. As of November 2020, the investor is finally back in the green (even though the index itself has not caught up).

Nikkei portfolios

Next, let’s look at how a hypothetical Nikkei 225 portfolio would have performed. We’ll look at two scenarios: the first is a lump-sum investment into the Nikkei 225 at its peak in 1989. The second is small, ongoing contributions to the Nikkei 225 over time. First, the lump-sum investor. Let’s assume we invested $300,000 at the Nikkei’s peak:

| Nikkei 225 total returns: portfolio value at year-end | |||||

| Investment | Dec 1989 | Dec 1999 (10 years) |

Dec 2009 (20 years) |

Dec 2019 (30 years) |

Dec 2021 |

| $300,000 lump-sum investment in Dec 1989 |

$300,000 | $156,117 | $100,238 | $272,318 | $343,516 |

This is terrible, as expected. This represents literally the very worst-case scenario, which is that we invested a lump-sum at the worst possible timing: the Nikkei’s all-time peak on December 29, 1989, right before the markets closed for the new year. There’s no way to sugar coat this: we’re screwed, and thirty years later, our portfolio still has less money than when we started, although after 31 years, we’re finally back in the green (in nominal terms, at least).

In reality, very few people invest in this manner. The results are also slightly less bleak if we invested our lump-sum at any time before or after the all-time peak. Instead of lump-sum investing, most people invest periodically, making small, ongoing contributions to their portfolio. This is sometimes called dollar-cost-averaging (DCA), although DCA technically refers to spreading out a lump-sum you already have over time. Instead, most people make ongoing contributions for a very simple and practical reason: they invest when their paychecks come in every month. This is what your 401(k) does, in addition to any additional investments you make outside of it.

For simplicity’s sake, we’ll assume that we made ongoing investments of $10,000 per year (so about $833.33 per month) into the Nikkei 225, again with our first investment on December 29, 1989 at the Nikkei’s all-time peak, and monthly afterwards. This equates to $300,000 total of contributions made after 30 years (note that technically, if we made our first $833 contribution in December 1989, then November 2019 actually represents 30 years of contributions. The table below shows portfolio values at year-end in December).

| Nikkei 225 total returns: portfolio value at year-end | |||||

| Investment | 1989 | 1999 (10 years) |

2009 (20 years) |

2019 (30 years) |

2021 |

| $300,000 lump-sum investor in Dec 1989 |

$300,000 | $156,117 | $100,238 | $272,318 | $343,516 |

| $833 montly investment starting Dec 1989 |

$833 | $99,827 | $158,459 | $617,545 | $802,280 |

In this specific scenario, the investor who made ongoing contributions outperformed the lump-sum investor by July 2003, after only $136,667 in total contributions. By the end of 2019, both investors have contributed a total of $300,000 to their portfolios (again, the 360th contribution actually occurs in November 2019). So 30 years later, the lump-sum investor’s portfolio value sits at only $272,318, whereas the ongoing investor’s portfolio sits at a healthier $617,545.

The chart below shows the portfolios over time, with the true 30 year (November 2019) portfolio values labeled:

Hypothetical growth of Nikkei 225 lump-sum and ongoing contribution portfolios with dividend reinvestment. For ease of calculations, the “resolution” of data used is monthly. Not adjusted for inflation.

The annualized returns of the Nikkei 225 does not adequately describe the behavior of an investment with ongoing contributions over time. This is due to the interaction between ongoing cashflows and the sequence of returns, leading to something called a money-weighted rate of return, or MWRR. In this particular case, the MWRR of the ongoing investor is 4.22% annually from 1989 to 2019, and 5.16% annually from 1989 to 2020. If you’re not quite familiar with this concept, you can take a look at my sequence of returns article. You can see another example of this phenomenon at work in my article on leveraged ETFs.

So lump-sum investing into the Nikkei 225 in 1989 performed very poorly, as expected. You would have been better off doing almost anything else with your money. If we made ongoing contributions starting in 1989, however, we fared much better, assuming that we consistently invested and held until at least 2013. I should also note that while the above chart was not adjusted for inflation, inflation in Japan has been extremely low for the past 30 years. If you were a Japanese investor, living in Japan, the purchasing power of the Yen has only decreased by approximately 17% from 1989 to 2019. After 30 years, the Japanese investor who made ongoing investments in the Nikkei 225 in 1989 fared better than not investing, even after inflation adjustment. This is because his 2019 portfolio has a nominal value of $617,545, and a real value of $535,234 (in 1989 terms) after inflation adjustment.

I also want to point out a few caveats. First, the returns are labeled in U.S. dollars for convenience, rather than Japanese Yen, although we’re not assuming any exchanges were made between the two currencies. The actual data used for the Nikkei index represent returns in Yen, not USD. The scenarios above assumes a Japanese investor, investing in their own domestic market, and living with inflation in their own country. The portfolio values are simply labeled in USD for an American audience. In reality, a foreign investor in the Nikkei 225 must take exchange rates into account to calculate their final returns in their native currency. The exchange rate between USD and Yen has fluctuated over the past 30 years, but it was approximately 140 Yen per USD in 1989 and 105 Yen per USD in 2020.

Secondly, returns and portfolio values were calculated as monthly averages, and the results above do not actually represent portfolio value on any particular day of the month. There simply isn’t enough data to calculate precise daily returns, so the “resolution” of the data is limited. Third, historical Nikkei dividend data before 2011 is notoriously difficult to find. I relied heavily on dqydj.com’s Nikkei returns calculator, linked previously. My results depend, on large part, on the accuracy of that calculator. Fourth, it was difficult to invest in the Nikkei 225 prior to 2001, as the first Nikkei 225 ETFs did not come about until 2001, although in theory an investor could try to replicate the index’s holdings individually. Finally, I am also not taking into account any trading fees, commissions, or expense ratios. So overall, while I am reasonably confident in the “big picture” story of these results, it is not meant to replicate the exact performance of any Nikkei portfolio.

Conclusion

Well, there you have it. The prospect of a Nikkei-like crash in the U.S. is unpleasant and would represent an unprecedented departure from what U.S. investors normally expect. All investments have risk. If you decide to invest, you must be prepared to accept this. But don’t let examples such as the Nikkei 225 scare you away from investing. Sitting on the sidelines has tremendous opportunity cost, especially if you’re young.

However, don’t stick to your assumptions based on historical returns as if they’re some immutable law of nature. For example, when I look at my time to retirement calculator or a compound interest calculator, I frequently assume that U.S. stocks will continue to average 10% annualized returns for my lifetime. I also assume that 10 years is plenty to wait out any market crash. But what if U.S. equities return only 1 or 2% over the next 30 years? How will that change your goals and timelines? Don’t plan your life, career, and retirement around an assumption that may not come true. Be flexible. Have contingency plans.

Also, when looking back through history, never look at just the price of a stock market index alone. Over long periods of time, dividend reinvestment accounts for a significant chunk of portfolio growth. While dividend reinvestment does not “save” the Nikkei 225 from being a bad investment in 1989, it does make the losses slightly more bearable.

The Nikkei 225 also shows the importance of diversification. Obviously, picking a single stock is not diversified, but many people are happy with the diversification they get from a broad market index, such as the S&P 500 or a total U.S. market index fund. Japan’s case shows, however, that you don’t want to put all your eggs in one basket, even if that basket is an entire country. International investing is easier now than ever, with widespread availability of international index funds. While most American investors gravitate towards U.S. stocks and index funds, there are many good arguments for including international equities in your portfolio.

Finally, context is important. The Nikkei enjoyed a decade-long bull run prior to the 1990 collapse. Investors who entered the market before 1989 saw their assets increase multiple-fold in the 1980s. Of course, the drop from December 1989 looks precipitous, but most people do not experience extreme outliers in luck or timing. Yes, it is possible that the unluckiest person in Japan somehow invested a single lump-sum into the Nikkei 225 on December 29, 1989, never invested again, and then withdrew his investment 20 years later at its nadir in 2009 with only 1/4th of his original money. But if he used the same investing practices that many of us do today and invested steadily over time with every paycheck, his portfolio still grew in both nominal and real terms after 30 years, even though the Nikkei itself has yet to recover.

Don’t let these worst-case scenarios keep you awake at night. For all of the above reasons, I don’t worry about the U.S. stock market going the way of the Nikkei. I believe that if we invest consistently, diversify, and wait 30 years or more, we should be fine. As always, thanks for reading and happy investing!

Update: this article has been translated into Chinese by TNL Media Group. Click here for the Chinese version of this article.

Bank failure dominates headlines.